Priceless works of art and antiquity can be captured by anyone using just the phone in their pocket. Is this ‘theft’ or a new dawn for the audience experience?

Over the year, museums and attractions have enjoyed an ever-evolving relationship with personal souvenir photography. At first, it was forbidden, then mildly tolerated. Now it’s positively encouraged, with the right accompanying #hashtag, of course.

However, that new-found comfort with visitor photography is about to be tested again as we enter a new era of photographic 3D capture.

A new generation of smartphone-based apps designed to help survey and capture the built environment has inadvertently equipped visitors with the capability to “steal” an entire exhibit, gallery, or museum. In a matter of minutes, high-resolution 3D models can be captured, shared and even sold online.

Should we prevent this? Can we even realistically do so? Or should we embrace this seemingly existential threat as an opportunity to redefine the visitor experience for the new 3D age?

A view from La Gras

The first known photograph was taken by Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. Ever since he captured that first grainy view from the window at La Gras, it’s estimated that humankind has taken a staggering 12.4 trillion photos.

Equally staggering is that 1.8 trillion of those photos were taken in the last year alone — some 14%. Even more astonishing still is that 95% of them are attributable to a camera-equipped smartphone (so ubiquitous has that device now become).

And this exponential rise is showing no signs of slowing down.

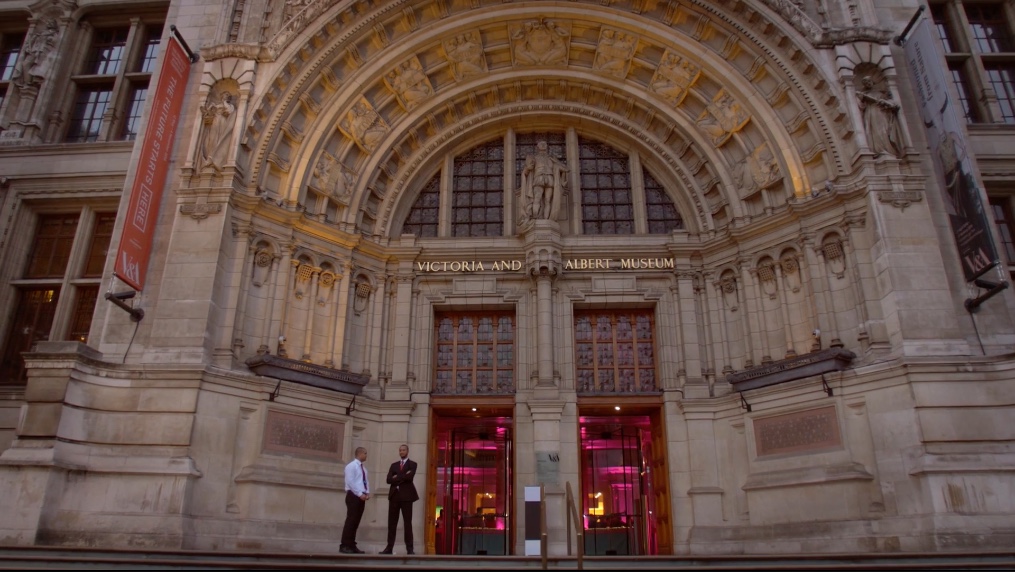

These mind-boggling statistics are played out every hour of every day inside any museum, gallery or visitor experience the world over. So much so that Insta-worthy moments are now routinely baked into every new experience design brief to positively encourage social souvenir photography and augment marketing efforts with a little extra ‘organic reach.’

But it wasn’t always this way

As mentioned earlier, personal photography was heavily curtailed, if not outright banned, inside gallery and museum spaces for decades. Just like the many illustrators and artists who believed the invention of photography in the late 19th century signalled the end of their careers, photography in visitor spaces was initially seen as a threat. Its ability to capture something unique and reproduce it undermined the very purpose and value of these places and their exhibits.

(We should acknowledge that many exhibits are fragile and can be irreparably damaged from uncontrolled flash photography, but even this understandable restriction cannot explain the many years of forbidding any forms of personal photography.)

Then we entered the digital age in the late 1980s. Cameras became smaller and more inconspicuous, and personal photography was tolerated as the equipment was harder to intercept in the bag check area. But it was with the arrival of the smartphone in 2007 that souvenir photography exponentially exploded. Finally, the attitude pivoted towards tolerance and advocacy in this brave, new ‘social age.’

A decade later, our social feeds now play an important role in our lives. We receive a constant stream of visual storytelling and inspiration from a mix of friends and brands. More recently, photo streams have yielded to video streams with the rise in popularity of platforms like Snapchat and TikTok. Now, no marketing strategy is complete without social assets, either self-published or handed to a new generation of influencers to help drive interest and footfall.

A 3D fairytale is on the horizon

We’re on the cusp of the next era of visual storytelling. We are moving into the 3D age, with handheld volumetric capture becoming as easy as snapping a 2D photo and 3D content becoming increasingly commonplace and shared as much as photography and video have been to date.

You can now quickly and easily capture detailed 3D replicas of physical objects and spaces that can be viewed, manipulated and even experienced at a human scale by others. Previously images and videos only captured what the camera was pointing at, but these volumetric 3D captures can capture everything.

Three technological advances have fueled this latest shift:

- Smartphone dual-lens cameras and LiDAR sensors.

- Affordable, cloud-based computer-vision capabilities that can quickly process large amounts of high-resolution photography data.

- Super-fast 5G networks that connect the cloud and smartphone so the two can work together in near real-time.

There are two different types:

- Photogrammetry is the process of creating 3D model geometry from (usually) 2D photographs. By comparing two photos of the same subject taken from different angles, 3D geometry can be inferred from the objects detected within a scene. The more photos used, the larger, better and more detailed the resulting model.

LiDAR sensors, now appearing on more smartphones, augment that process by overlaying genuine 3D-scanned data from the sensor to improve those inferred 3D models and fine-tune the results. The result is a ‘mesh’ model of the captured scene, complete with textures wrapped around that mesh. For many museums and collections, this scanning is already used for archival purposes in the pursuit of digital object collections.

- Neural Radiance Fields, or NeRFs, are derived from the same image sources but use AI-powered neural networks to interpret and build the scene. The more source photography, the better the results. But in practice, much less source photography is required to build realistic models using photogrammetry techniques because AI can fill in the gaps.

LiDAR does not play a part here, and NeRFs are much less picky about their source photography. Even photos from different cameras, shot on different days, can be used to reverse-engineer a recognisable 3D scene.

The final result is very different, too. NeRFs are genuine, volumetric 3D point clouds of voxels (the 3D equivalent of the 2D pixel) rendered in real time. Hence, things like lighting and shadows are dynamic rather than fixed from the original capture.

NeRF technology currently trails photogrammetry, but the pace of improvements is breathtaking, with advances coming every week.

Batten down the hatches or fling the doors wide open?

The immediate reaction might be to lock all the doors and windows, ban smartphones (again), and redesign galleries to prevent 360-degree free roaming by the public.

Or, we can simply ignore this activity and hope it doesn’t proliferate any further.

But given the relentless march of smartphone capability and the pursuit of differentiation in the annual handset upgrade cycle, we’d postulate that it’s highly likely that 3D photo capability could soon be built right into the OS, leveraging those already built-in sensors and connectivity, and exposing this capability to millions.

Instead of trying to put the genie back in the bottle, let’s imagine what we could do if we actively leaned into this opportunity and embraced it, as we eventually did with personal souvenir photography. Whether it’s by creating digital twin experiences for those who cannot travel, extending the shelf life of shows and exhibitions, or reaching new audiences and markets through digital ecosystems, there are endless ways to take advantage of the new 3D world.

Here at Squint Opera, we’ve always leveraged the latest technologies to tell the greatest stories for the world’s greatest destinations, so we’re incredibly excited about the new 3D age. These 3D formats and possibilities should be seen as an opportunity and embraced for the incredible, immersive experiences they present.

Questions? We’d love to get in touch.