About Me

My name is James Merry. I’ve been working in motion graphics design and animation for 22 years – 15 of them at Squint/Opera. I have “severe sensorineural hearing loss” (aka I’m “deaf”), and I’m passionate about the creative ways in which we can design accessibility into media, both at home and in public spaces.

As Lead Animator at Squint/Opera, specialising in motion graphics design and animation, I’ve lent a hand to hundreds of projects over the years, contributing to internationally renowned attractions such as The Empire State Building visitors’ experience, Lift 109 at Battersea Power Station and Hong Kong’s Peak Tram.

I design everything from immense digital interactives, such as the Kaleidoscope walls as part of Oman Across Ages, to short animated films, like “Making the Met,” a set of films celebrating the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 150th Anniversary.

Let’s explore the (surprisingly fascinating) history of subtitles and discuss ways to seamlessly incorporate accessibility into contemporary and future media.

Vital as a subtitle

Subtitles have been around ever since movies were invented. Sometimes they are called “captions”, or “intertitles,” or sometimes even just “words on a screen.”

Too often, subtitles are a neglected afterthought. They are often even considered to be undesirable or a distraction.

But they are an essential accessibility feature for any audio-visual media. Many deaf people rely on subtitles to understand and enjoy television, cinema, games, exhibitions, music, and even radio. And in recent years, thanks to streaming video, subtitles have become more visible and acceptable in the mainstream.

Open captions

Open captions are burned into the footage and usually only consist of spoken dialogue. Open captions would usually be what you see in foreign-language films. But they can also be used as a world-building plot device to denote “otherness” (i.e., “Elf” or “Klingon” language). In the Marvel film “Eternals,” open captions are deployed so hearing audiences are able to access the deaf hero’s American Sign Language.

Closed captions

Closed captions are an additional track that runs alongside the video and the audio. It can be turned on and off.

There can be multiple subtitle tracks which may include different language options. Some subtitle tracks may be specifically written for deaf viewers. These include not only spoken dialogue but also descriptions of sound effects and music. Different colours can also be used so you know who is talking.

Neolithic subtitles

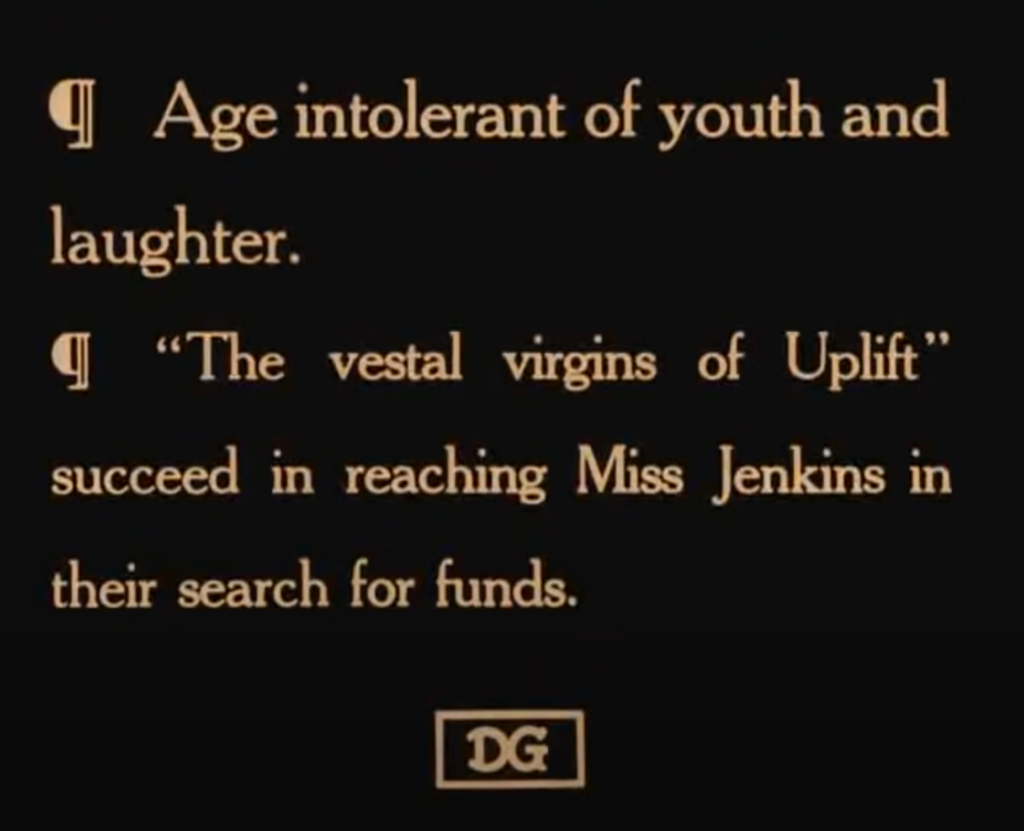

The first subtitles were invented alongside the earliest silent cinema movies. If there were dialogue, the audience would have to read it on the screen, whether they liked it or not.

Some early filmmakers were very creative with their subtitles.

“How it Feels to be Run Over,” Cecil M Hepworth’s 40-second epic from 1900, ends with the text, “Oh! Mother will be pleased.” These words look like they have been carefully scratched into the film itself, with only one frame per word, so you have to read it very quickly.

In his 1907 film “College Chums,” Edwin S. Porter uses animated text to caption a telephone conversation.

In “The Chamber Mystery,” by Abraham S Schomer (1920), the captions are written in comic book style speech bubbles. Unfortunately, this idea never really took off.

When the silent movie era ended in 1927, on-screen text very quickly fell out of fashion. If you needed subtitles, you were out of luck…

…Unless… you watched foreign-language films. Ironically, the rise of the talkies meant that subtitles were now needed so films could be exported to other parts of the world. This seems to have led to the conventional subtitles we know today: i.e., two lines of text at the bottom of the screen, tucked out of the way.

Television text

When I was growing up, subtitles on television didn’t really start happening until the mid-1980s. Before, if you wanted to watch television, you would just have to put up with not understanding what anyone was talking about.

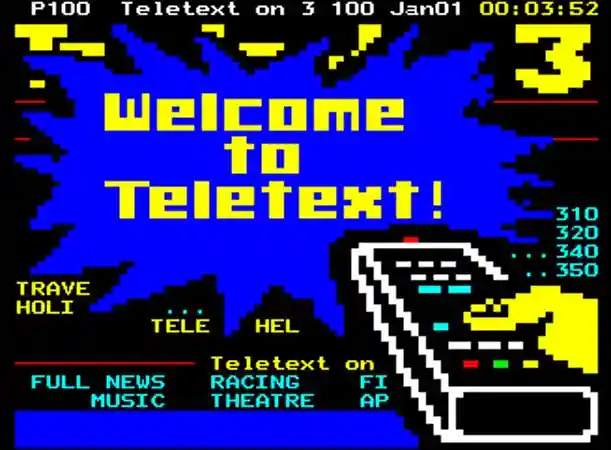

At some point, an enormous new television set from Radio Rentals appeared in our house, which came with a remote control. And it also included an insanely advanced new technology known as “Teletext.”

Teletext was amazing. It was like a proto-World Wide Web. It had hundreds of pages, navigated by punching numbers into the remote control. It had the news, football results, package holiday deals, jokes and even quizzes.

Far and away, the BEST thing about Teletext was if you punched in the number “888” – you’d get subtitles! (sometimes).

At first, only a few television programs had subtitles, and they were usually pre-recorded. Subtitles for live TV, such as the news, were rare because it was impossible for anyone to type fast enough.

Eventually, software was developed which was able to convert, on the fly, the phonetic symbols from a stenograph machine into readable English. This could then be transmitted as live subtitles via Teletext.

Very slowly, over the years, more television programs became subtitled. Most television programs in the UK now have subtitles, but there are still some odd exceptions.

Subbing on the silver screen

It used to be that the only way to watch a subtitled movie at the cinema would be to see a foreign-language film. These days however, most cinemas use digital projection technology, so they can just turn the subtitles on and off. Now it is possible to find special subtitled screenings of the latest mainstream movies at your local multiplex. But these screenings are not easy to find, and they are usually shown at funny times, such as 11:30 am on a Tuesday morning – so, actually, not really accessible to anyone who has a job.

In fact, paying for tickets to see a mainstream movie advertised as “subtitled,” only to find that the cinema “forgot” to turn the subtitles on, is a well-known universal part of the overall Deaf ExperienceTM. I have even seen movies begin with subtitles, -only to see the subtitles turned off due to complaints from hearing customers.

Gaming

Modern games can have many hours’ worth of spoken dialogue in them, and it’s vital to include options for subtitles so deaf players can follow along. Players will also need to know what the sound effects are and what direction they are coming from, as this will affect the decisions a player will make in the course of the game.

Some games (such as Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, below) include arrows to indicate what direction the sound is coming from.

Performances, exhibitions and live events

Like cinemas, every now and then, many theatres show subtitled versions of their productions. Stagetext is one organisation which specialises in providing captions for live performances. Usually, these are displayed on a screen next to the stage. These captions have made many live events accessible for deaf people that would not otherwise have been.

This is great, but like cinemas, subtitled performances are rare and difficult to find. And once you’ve found your subtitled play, it can be an effort to be constantly switching eyeballs from stage to captions, back to stage, and so on. You also have to make sure you get a good seat. If you sit too far away from the captions, you won’t be able to read them!

The National Theatre has been experimenting with smart caption glasses for some performances. Attendees can borrow them to watch the performance and see subtitles projected onto the lenses. It’s very clever, and it seems to work well for some. Others have found them to be uncomfortable, and some resent being asked to wear even more tech so that they can have the same access as hearing people. As the technology becomes more seamless, however, perhaps the experience of using caption glasses will improve.

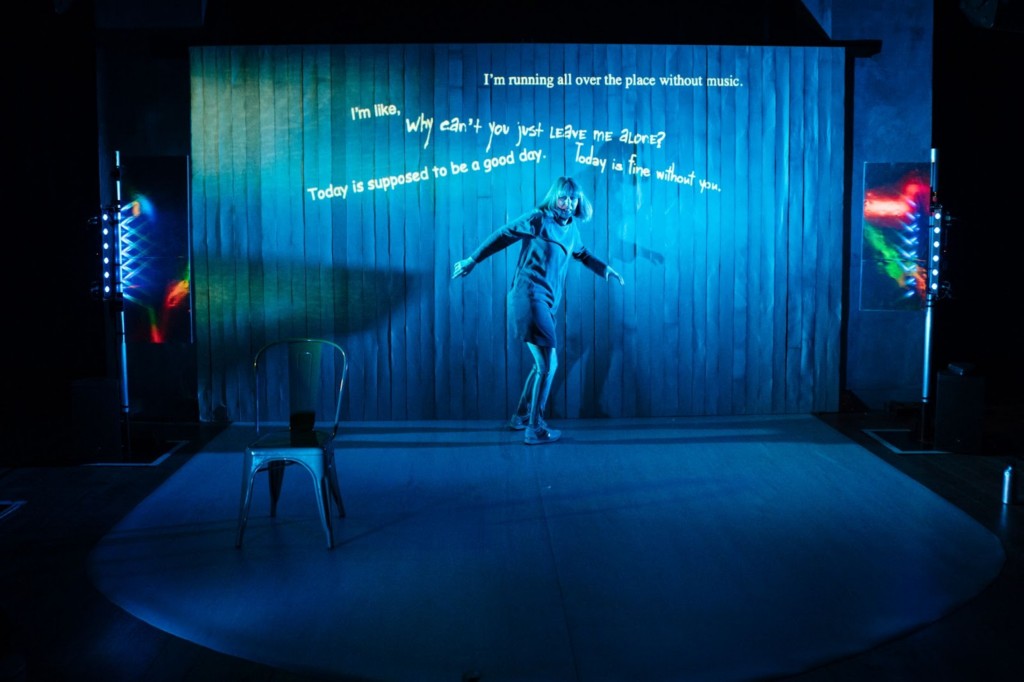

The best captions are when artists incorporate them directly into the production design. A great example of this is “Augmented,” a play written and performed by Sophie Woolley in 2020. Captions are projected onto the backdrop. They become an integral part of the performance, with animations and effects to help convey the narrative and emotions.

Museums, exhibitions, and theme parks are increasingly using audio-visual media as part of their narrative experience. These also need subtitles – it is surprising how often, even in this day and age, subtitles are not available.

A text message to the future

It’s great that subtitles have become more visible and acceptable everywhere in recent years. This is largely due to a combination of creativity, technology, and disability equality laws.

Subtitles can even be automatically generated via voice-recognition software, which is amazing. They can save hours of work (although you must check them with human eyes for errors and instances of random inappropriateness).

So it’s always disappointing when we find ourselves in a situation with no access to subtitles. There’s no reason not to have them!

But there’s more…

The creative early subtitle examples shown at the beginning of this article, and the more recent experimentation in live performances, show that subtitles can be far more than just a box-ticking after-thought. When subtitles are considered, designed, and integrated right from the beginning – they can also add extra value for everyone, not just deaf people.

AI speech recognition systems are already being used to help transcribe subtitles. Maybe we will start to see generative AI also assisting with the crafting and presentation of creative subtitles too – this could be especially interesting for live events and performances.

This piece was written in support of Deaf Awareness Week 2023, which runs from May 1st-7th. This year focuses on “Access to Communication” and aims to address the communication challenges faced by the 11 million people in the UK who experience hearing difficulties.