How to design a better tomorrow

Dystopian futures are part of our collective imagination, and you don’t have to look far to find examples of them in pop culture: Terminator, Blade Runner, The Matrix, Ready Player One — the list goes on. But representations of the future needn’t scaremonger in this way; they also help us imagine what we want for the next generation.

With the right vision, architects, designers, and developers are equally capable of creating a tech-driven future that will benefit us all.

Communities come in many forms, from isolated rural villages to sprawling urban metropolises or online global networks. Whatever form they take, future innovations like AI, robotics, digital interventions, automation, and integrated transport networks will be instrumental in creating the connected and harmonious communities we all aspire to.

We must embrace and understand this oncoming wave of innovation to elevate our neighbourhoods, connect us, extend our environments and empower our shared history.

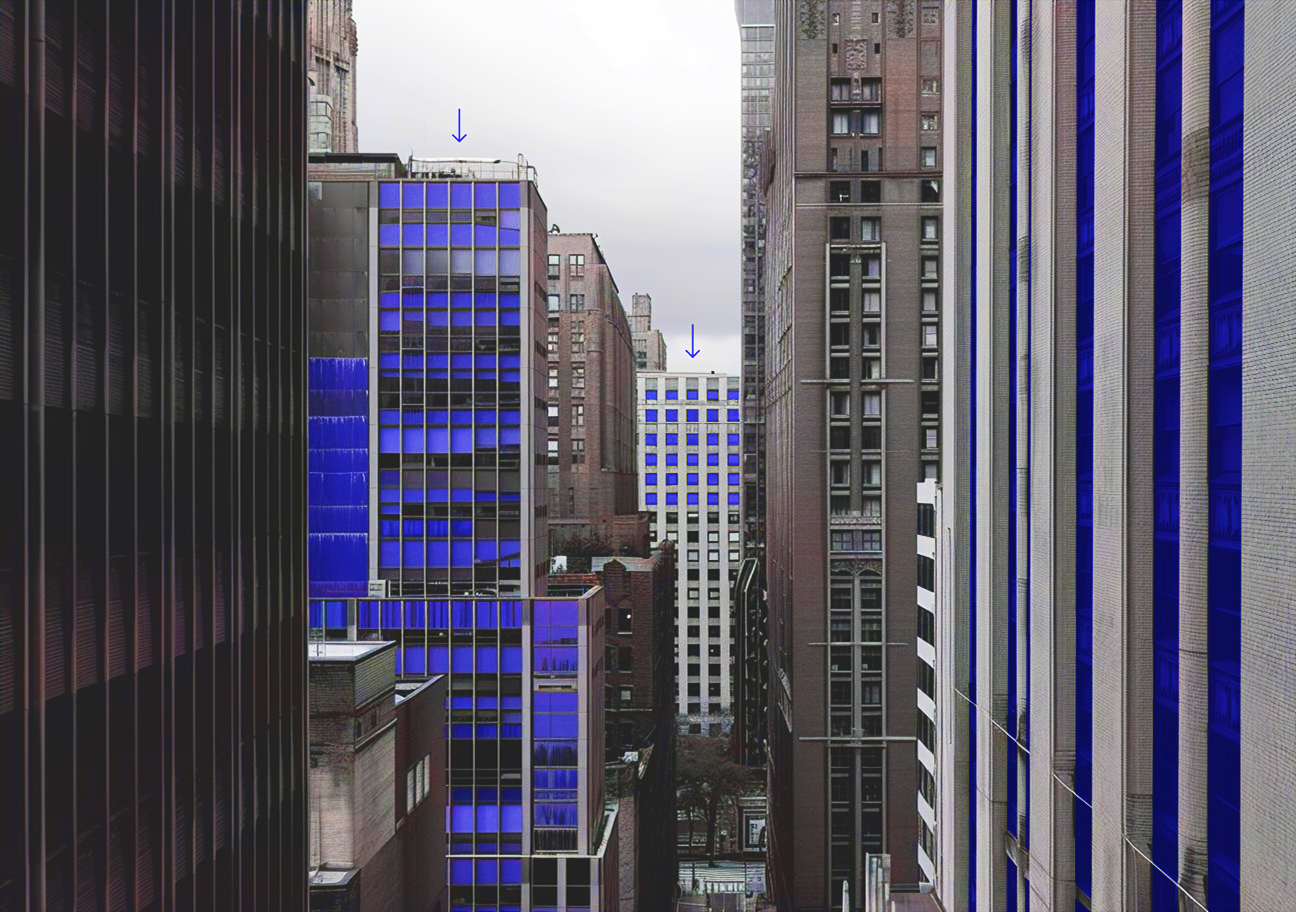

Revitalising our town and city centres with immersive experiences

Immersive technologies offer ways to transform our struggling town centres, impacted by changes in consumer/worker patterns & the pandemic, into what the New York Times called ‘The Playground City’: a mixed-use destination that brings communities together in urban environments.

RIBA’s (the Royal Institute of British Architects) recent book, ‘High Street’, indicates that the UK has up to 40% more retail space than it can support. This oversaturation has led to unoccupied spaces and a decline in the traditional town centre, especially in smaller and less economically developed regions.

We can enhance social connectivity and mental well-being by transforming our urban spaces into interactive ‘playgrounds’, that give families and friends space to catch-up, learn something new, and most importantly have some fun.

Younger generations are a key demographic to enable urban renewal; they expect experiences that future urban spaces will have to deliver if they are to survive. We predict an increase in many former industrial, office and retail spaces reinventing themselves to attract visitors. We’ve seen this at the Bussey Buildings in Peckham south London, where a vast Victorian sporting goods factory has been convered into a mulit purpose creative space offering pottery classes, secret cinema clubs, music venues, art studios & galleries.

An example of immersivity as a tool for urban renewal is Battersea Power Station, which underwent massive redevelopment, transforming it from a near-derelict site into the epitome of an urban playground.

Squint created immersive media for Lift 109 at the iconic power station; dynamic animations, gamification, immersive media and soundscapes enhance the observatory experience from arrival to the gift shop. Beyond just augmenting the experience, we strived to create a narrative throughout that educates audiences on the rich heritage of Battersea and its impact on surrounding communities and London as a whole.

In the future, revitalising neglected urban spaces with immersive tech will become a ubiquitous practice. In London, we are already seeing the trend emerge. The Outernet was London’s most visited site in 2023 and is Europe’s largest digital space; at Drumsheds Tottenham, a former IKEA has been converted into a three-storey superclub, offering immersive audio-visual experiences.

But what use are these exciting urban initiatives and activated heritage sites if everyone can’t reach them? We must integrate our transportation networks into communities in innovative and eco-friendly ways to ensure the future is accessible to all.

Next-gen transportation

Future developments will be built for people, not cars. Improved mobility systems will reorganise communities, ending the model of the central business district ringed by suburbs. Instead, future communities will consist of hyper-localised micro-hubs, 15-minute communities connected by e-bikes, e-scooters, walking, and high-speed transportation networks.

Although cars will still exist in the future, they’ll likely be electric and autonomous. They may be relocated to underground or elevated roadways, allowing streets to be remade for pedestrians, or the rise of autonomous buses and other forms of public transit may essentially phase them out. We’re already seeing progress on this front, with companies like Cavnue designing the vast amounts of infrastructure needed to accelerate the development of autonomous vehicles. We’ve helped launch Cavnue’s brand and look forward to the affordable, high-quality public transit their work will usher in.

Super high-speed transportation is in the works. The American company Hyperloop One aims to use maglev systems in underground vacuum tubes to move cargo trains at hypersonic speeds. In our project for them, we delivered a film that imagined a traveller’s journey on a high-speed Hyperloop linking Dubai with Abu Dhabi. Once completed, these projects will mitigate the environmental damage done by cars and aeroplanes.

The downside of using exciting new technologies for transit is that they can be prohibitively expensive, creating a gap between urban and rural haves and have-nots. London, Los Angeles and Dubai might soon have high-speed rail, but what about the communities hundreds of miles away from metropolises?

The key to connecting isolated communities may come from above. Several startups, like the French company Flying Whales, are designing clean-energy-powered helium airships to connect rural communities with opportunities in urban centres. Meanwhile, the British company Hybrid Air Vehicles is planning its Airlander 10 ship to replace shorter national aeroplane flights and, most importantly, transport people on less-served routes; it’s the return of the Zeppelin!

Intelligent transport systems, such as autonomous traffic rerouting during roadblocks, will elevate our existing infrastructure and public transit options, leading to lower emissions, less gridlock, more connections on current lines, and seamless movement through regions.

Personal and public vehicles themselves have reached a pivotal point. We expect that vehicle interior cabins will become hubs for entertainment, productivity and socialising. You’ll be able to take meetings in your autonomous EV, have a coffee with friends or even chill and watch a film on long journeys. An upshot here is that the concept supports shared ownership. Friends or colleagues can club together to get a vehicle they can all use and enjoy together.

Beyond seeing fewer journeys by car, we predict the very nature of what we understand as transport networks will change in the future; perhaps the ultimate step forward will be simply getting from A to B in a 15-minute walk, surrounded by trees and wildlife.

How to connect communities using virtual personas

Avatars and augmented reality hosts represent a transformative leap in personalising and enhancing communal experiences, especially in cultural spaces like museums.

Think ‘Night at the Museum’ at a neighbourhood level.

Your local visitor centre might have an AI-powered, animatronic character based on a notable historical figure or a regional town hall may have a virtual mascot that shares details about events and community organising. It’s not a replacement for humans but a way to augment existing resources and bring a playful, gamified energy to local interactions.

Avatars are already being used in institutions such as the German Mining Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art; these virtual guides personify the institution and offer interactive tours tailored to visitors’ specific interests, knowledge levels, and even location in the building.

They’re not just guides but companions, learning from our preferences in conversation to steer us towards exhibits we’ll love, providing information and context in a multisensory manner that caters to various learning styles.

At Le Musee de la national Marine in Paris, Squint created sign language avatars, which ensure every visitor can fully engage with exhibits, regardless of their cognitive or physical abilities.

Beyond museums, avatars are making inroads in a variety of sectors. The Bitmoji app helped teachers inject personality and emotion into their remote classes during the pandemic. The Sphere in Las Vegas currently offers an ‘avatar scanner’ that uses 3D polymetric scans to create visitor avatars.

Aurora, the highly advanced humanoid robot that permanently resides in The Sphere lobby, is a glimpse into the future of android hosts. She serves as a humorous spokesbot and interactive guide for visitors; equipped with AI and voice recognition capabilities, the android feels uncannily ‘conscious’.

In the future, Avatar companions, like those imagined in Liquid City’s short film ‘Agents’, could become integral parts of our daily lives, coexisting with us and enhancing our interactions with the world around us.

Tailoring everything to everyone is thoughtful, to support individuals to nurture the bigger picture, but what if we are not happy or healthy? Technology can help create a foundation for our well-being.

Creating virtual environments through digital twins

Virtual environments refer to simulated digital landscapes experienced through VR, AR and video games. VR platforms like Oculus Quest and PlayStation VR offer immersive experiences, allowing users to walk through virtual forests or dive among coral reefs. Meanwhile, AR applications like Pokemon Go overlay interactive naturescapes and virtual wildlife onto the real world, incentivising people to explore their local area, exercise, and get out into nature.

Beyond pure entertainment, these virtual nature experiences have been found to reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance cognitive function. They offer a unique way for people, especially those with limited access to the great outdoors, to connect with the natural world and benefit from its therapeutic effects.

Our HomeForest design draws on the biophilia hypothesis and shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) to bring the therapeutic effects of nature indoors. HomeForest, the 2021 Davidson Prize winner, proposes a digital ecosystem that blends seamlessly into the day-to-day, sensing when you need a break and influencing serendipitous moments through birdsong, forest canopies, and dappled lights. By creating a generative forest of the home and tapping into existing home technology, the digital twin infuses well-being into an individual’s routine, enhancing their perceptions of their living space.

Fundamentally, Homeforest could happen now and for everyone, catering to each individual’s means and desires whilst requiring no new city typology.

In the future, virtual twins will also help communities preserve their heritage, as with the small Pacific island nation of Tuvalu. In its struggle with the existential threat posed by rising sea levels, Tuvalu has undertaken an initiative to create a virtual twin of the nation to catalogue, map and save as much of the island as possible, becoming the world’s first fully digitised country in the metaverse. This initiative, which includes an immersive platform where future generations can interact, will help ensure that Tuvalu’s history, culture, language, and social fabric survive, even if its physical land does not.

HomeForest and the Tuvalu project are part of a new generation of digital twins. They join a broader set of use cases for this groundbreaking tech, from manufacturing more ecologically friendly cars to tools allowing patients to visualise their ailments for better communication with doctors. With the right creative vision, digital twins will continue finding new uses that enhance people’s connections to the environment and their communities.

But none of this means anything if we lose who we are along the way. Technology will help document our past and imagine our futures, bringing collective stories and memories to life.

Helping under-represented communities tell their stories with AI

With all the talk about generative AI stealing people’s jobs and manufacturing misinformation, it may be surprising to think of it as a community-building tool. However, we’ve found that AI can be especially helpful for filling knowledge gaps and enhancing understanding and accessibility.

It’s quickly become a tool to support projects of all sizes, particularly for small communities and groups with limited archives.

Squint harnessed AI to address limited historical archives for the Muskoka Steamships and Discovery Centre in Ontario and the Oman Across Ages Museum in Manah, Oman. In Muskoka, we merged historical accounts with modern photos to reconstruct the life of settlers in the area during the 1800s, which visitors explore through a video game; we also used AI tools to reconstruct the landscape and lake scenes of poor-quality, tightly-cropped historic photographs of the community’s iconic steamships. In Oman, we used AI to upscale personal archives into formats that could accommodate the giant exhibits. Through AI, we successfully filled historical gaps in both projects.

AI will continue to bring history to life for underrepresented communities that have had their artefacts lost or destroyed, or that never had the chance to create archives in the first place. It could be employed in the kinds of archival redescription projects that scholars are doing at Princeton University and Carnegie Mellon University, helping to identify unnamed figures, amplify underrepresented voices, and make narratives of marginalised communities more accessible to the public.

In the future, museums may feature AI-powered visualisation rooms where visitors can explore “what if” scenarios. Imagine a visual thesaurus meets Midjourney cinema room where we could be immersed in alternate histories and futures, a world without Romans or where dinosaurs still roam. These visualisation rooms could bring lost community memories and ancestral stories back to life.

The future belongs to everyone.

Designing our future communities is challenging because we want to uplift everyone simultaneously. Groundbreaking new technologies usually come to the well-resourced first, and they aren’t always designed with everyone in mind. The same science fiction films that warn about robot takeovers caution us not to create futuristic cities that cater to the elites whilst locking out everyone else.

Luckily, the sci-fi genre also offers positive examples, moments where technology is used for good. From the ambiguous utopia of Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel The Dispossessed to the virtual assistant Samantha in the movie Her, we can see models of societies that use technology in imperfect but human-centric ways.

Squint/Opera has been pioneering the use of innovative tech in our projects for 20 years. We know a better future is possible with the thoughtful and creative use of AI, mixed reality, avatars, virtual twins, next-gen transportation, and other innovations.

At Squint, we always aim to give present-day communities a voice while keeping future generations in mind. Most importantly, we know that the communities we’ve always dreamed of will begin with the groundbreaking designs of today.