Amid the 2023 hype rollercoaster surrounding the metaverse and now AI, another less heralded tech revolution has been quietly taking place this year. It’s the understated sibling to its attention-hungry relatives, and like them, it’s been around for a while, but with one crucial difference – it’s been through previous hype cycles, has already languished in the valley of despair, and is now emerging into the light of actual commercial applications.

The return of the virtual twin.

Long pigeon-holed as the preserve of engineering or aeronautical science, virtual twins are no longer just mathematical models brought to life in 3D, measuring aerodynamics or energy flows, but increasingly they are also experiences in themselves, platforms for storytelling, and core communication tools.

For years it’s been predicted that things would move in this direction, but that view hasn’t been shared by all. The charge sheet reads as follows: first, it’s not clear what the use cases are. Second, we’ve been here before – many clients have been burned by poor-quality virtual twins that didn’t work reliably or look good enough – a hardcore waste of money. Third, what’s the point of a virtual twin? What’s wrong with the good old plywood model? And last, it’s basically an engineering thing, isn’t it? – only really useful for planning factories or industrial processes – in other words, a technical tool used in technical contexts.

Whichever side of the debate you fall on – booster or sceptic, one fact we do know (and the reason for writing this article) is that we are being asked to make these twins more and more. From a trickle in 2020 to a steady stream in 2023, they now form a core part of our business. Below we set out why we think that’s happening, the main ways that we and our clients are using virtual twins, and how we see them forming the backbone of our practice in the future.

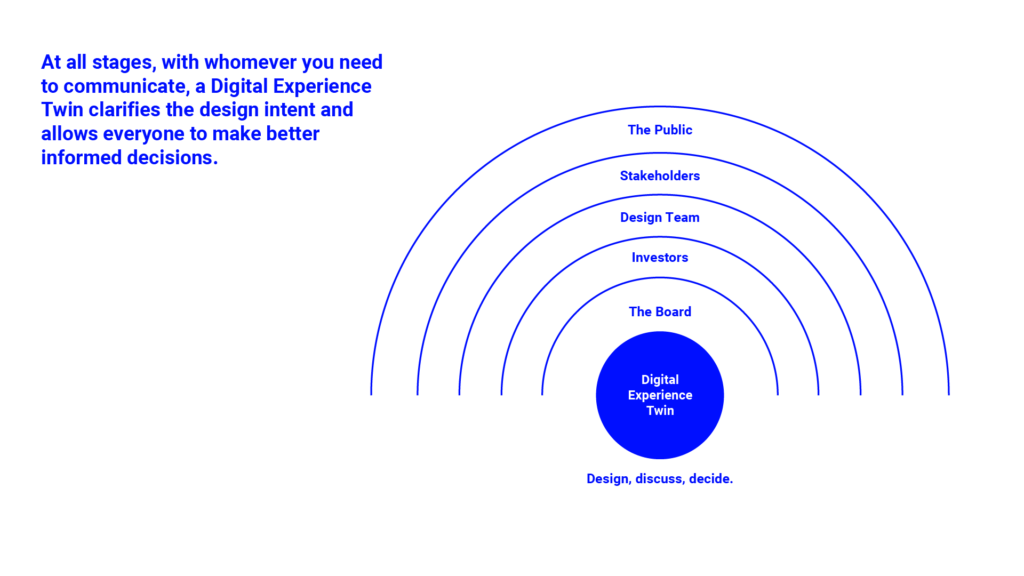

Design, Discuss, Decide.

One of the key aspects of our practice is that we make what we design. In other words, we don’t just ship a design or storyboard to a contractor. We take it all the way through to the finished experience, often encompassing complex media, technology, and interactivity, all at scale.

The advantage of working this way is that we can guarantee the quality of the finished product, but it also comes with a couple of risks. First, there’s no one else to blame if it doesn’t work – we can’t point the finger at a contractor and say it was someone else’s fault. The second risk inherent in the kinds of immersive experiences we make is that they are either magical, or a terrible disappointment.

All the tech and staging has to work in harmony – if anything buffers (the dreaded wheel of doom), fails, or is out of place, the experience turns from magic into intensely frustrating. So we have an on/off problem – it’s either a hero or a zero.

These binary outcomes – hero or zero – make it critical that we test before we proceed to build something out. Virtual twins are the current best way to do this, from big picture questions like emotional impact, overall wow factor and so on, to smaller details like the volume of the sound or scale of a button or graphic. Doing it this way means that we take a huge amount of risk out of the project, both for ourselves and our clients.

The first project we truly realised the value of a virtual twin for was the Empire State Building. Overall it was a whale, both in scale and complexity, but also in terms of financial risk. Once up and running, the exhibition is open from 8 am to 2 am and welcomes over 30k people through the doors every day. Visitors come from all over the world, so the exhibits need to be in different languages. Within some of the spaces, for example, the King Kong room, and the Construction Gallery, multiple projections on several sides of the room have to work in harmony.

The sign-off process with the client group was arduous and time-consuming, with multiple suppliers and vendors. Our typical – 2D – review process wasn’t really working – identifying areas of high priority was difficult, and we were all getting bogged down in details.

We switched to the virtual twin as the primary review tool, and it changed everything. Immediately it became clear to everyone what was working well and, more importantly, what was not. The decision-making process went from a snail’s pace to (relatively speaking) a cheetah sprint. Confidence in the project rocketed, and the mood of the overall team went from ‘somewhat nervous’ to ‘it’s going to be a hit’ (it has been the top Trip Advisor rated attraction in the USA in 2022 and 2023).

We took what we learned on the Empire State Building project, and applied it to another project on the other side of the world, the Peak Tram in Hong Kong. The tram, which runs from the base of Victoria Peak all the way to the top, is the oldest mountainside railway in Asia and a top attraction in Hong Kong, with 17,000 visitors per day, so we faced a similar set of challenges to the ESB – the attraction is always on, and always packed. The risk of getting something either creatively or technically wrong was high.

Our concept was to create a real-time 30ft animated landscape along the wall and ceiling of the departure area that would depict the pre-human environment in Hong Kong, complete with flora and fauna. Additionally, we had to deliver the project during Covid, and with Hong Kong in lockdown for long periods of time, site visits were out of the question. Without the virtual twin, the project would have been near impossible. It allowed us to judge scale, movement, colour, light levels and sound so that when we got to install and launch, it was a (as much as these things ever are) seamless success.

The ability to virtually test before the build is priceless – it gives the option to place an audience within the experience to get feedback or modify proposals, it gives clients the ability to understand the impact moments, and the technical team to spec out the right equipment. It profoundly changes the design process, democratising it (everyone has a valid opinion about spaces – it’s just intuitive once you’re inside it) and brings it nearer to agile software development. No longer are there gated or staged decision points; it’s more of a ‘test and refine’ model. You can try out options, test assumptions, (perhaps) think more radically, and trial whether that audacious but unconventional idea could actually work.

Switching reviews from 2D formats to 3D immersive formats will be the biggest evolution in the design process since the invention of paper. At all stages, with whomever you need to communicate, a virtual twin clarifies intent and allows everyone to make better-informed decisions. The promise of really immersing in a future place will mean more can be resolved prior to building. The building stage will always throw up the unexpected, but the twin is an amazing tool for the builder, too – to understand what the designer is aiming at, taking away the uncertainties and vagueness of language.

Three tech trends are coming together to enable this revolution – spatial computing, advances in gaming engines like Unreal and Unity, and pixel streaming technology.

Spatial computing will give us personal devices (like the Apple Vision Pro) that can interpret, respond, and interact with the real world around us. The new generations of gaming engines are delivering Hollywood-level impact and fidelity. They are increasingly automated, enabling boutique studios (like us) to make environments that before would have been the preserve of the industry gorillas.

Pixel streaming means cloud-based broadcast technologies that can reach anyone, anywhere.

The same twin we use in the design process can also be used down the line for communications. In our project for BIG Architects and Toyota, launched at CES, we created an on-stage presentation as well as an immersive installation, both using the same virtual twin of the future city.

For the Trojena project, we used our twin as a backdrop on a virtual production stage (see Alice Britton’s – ‘Max out the volume‘), enabling us to shoot perfectly detailed and realistic shots of the future location using the lidar-scanned mountainous landscape. In that respect, the twin is like having a permanent set you can go back to countless times and shoot different films on.

In the future, we see pre-programmed avatars being introduced into these simulations, simulating patterns of behaviour and usage, and eventually being used to predict how design changes would impact people’s lives for the better.

Our goal is to use these simulations to improve both the quality of experience of a place – by ensuring it’s been tested before it’s built – and its environmental performance.

We’re starting to see signs that the twin may prove to be a genuine game changer, rather than just another tech hype-cycle.